Half-born

Publication of my novel is in itself a story full of highs and lows

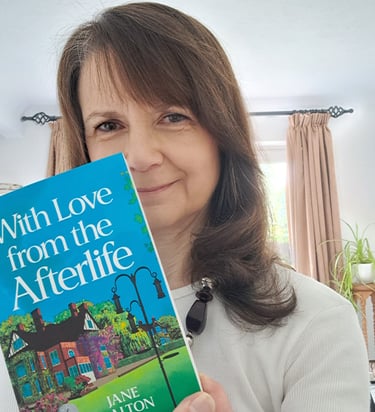

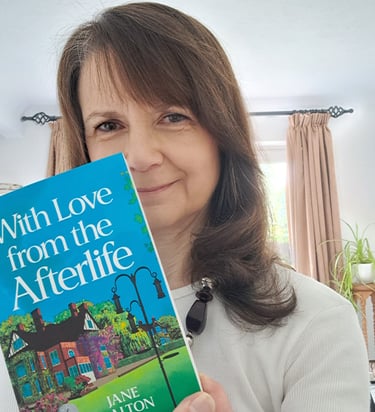

Jane Dalton

9/22/20258 min read

For authors, sometimes getting your debut novel published is not just exceptionally difficult, it's complicated, too.

My novel is half-born.

And its part-birth has saved me from being dashed on the rocks of despair.

My first novel, which I began when I was eight (so no hyperlink here), made it only to the third chapter, my characters left for ever suspended in crisis mode. But my secret ambition to write a novel and have it published continued to slowly burn, unseen, while I got on with life's usual stuff.

When I finally did finish writing one, I knew little about the art of fiction-writing, and it came out as funny and serious, light and dark, offbeat and unorthodox. Not at all what I'd long imagined my debut novel would be like. It rather took me by surprise.

Knowing agents and publishers were overwhelmed with manuscripts, I was prepared for rejections. But still, when they came, it was of course hurtful. Finally, a small but growing publisher called Neem Tree Press replied saying they loved my draft and wanted to take it on. I was elated. I had waited a lifetime to see a book I'd written in print so this really was a dream come true. And I liked Neem Tree Press. It was an all-women company whose list included work from overseas, as well as novels that did not neatly fit formulas. The founder told me of her ambitions to build a company as large as one of the big five.

But while I awaited my due publication date, without warning came news that Neem Tree was joining forces with a crowdfunding publisher called Unbound. Authors such as me were assured that contracts would be honoured and publication would still go ahead. I wasn't especially happy that my book would appear to the world to be one supported by crowdfunding when it wasn't. But at least the Neem Tree Press name would remain, becoming an imprint of Unbound. It was exciting to see my book on Amazon, marked as due out in January, and on platforms such as Barnes & Noble. Friends started preordering copies on the Unbound website.

However, when my emails to Unbound as well as Neem Tree people started to go unanswered, I suspected all was not well. When even urgent messages were ignored, I realised my hopes were hanging by a thread.

I knew that if the worst happened, I would be devastated. I pictured myself in tears, feeling a failure, curling up into a ball. I couldn't face sending my work out to yet more agents only to receive another round of rejections, adding to the 25-odd I'd already had. Besides, time was marching on, and at the timescales the conventional publishing industry necessarily works to, I would be an old woman before seeing my debut novel in print.

Yet when the confirmation came of the collapse of Neem Tree/Unbound, something else surprised me. I wasn't devastated. I was resigned. The world didn't want to see my life's work and could carry on perfectly well without it. But it was embarrassing that friends and family who had been kind enough to support me by preordering for a copy were now out of pocket, their money swallowed up by the failed Unbound.

A friend who is a successful author of young adult fiction suggested I fund a limited print run strictly for people who had paid upfront but who had lost out. At the same time, another writer friend who is in a self-publishing cooperative kindly invited me to join them. Both friends recommended using IngramSpark, a large reputable self-publisher. It seemed to me that paying for a limited print run was the ethical thing to do.

Neem Tree Press used to work with an entertainment agency, Viv Loves Film (VLF), which specialises in pitching ideas, including novels, to film producers, and, knowing how authors had been left bereft, was keen to take us on as our agent, for which I was grateful. It has given me a further glimmer of hope that With Love from the Afterlife may yet find a home with a publisher.

Before Unbound's collapse, I was signed up to appear at Cuckfield BookFest, on a panel of authors speaking about - aptly enough - the challenges of publishing, a subject that took on more significance after the company's demise. I was likely to be in the unfortunate position of being an author talking about publishing without having any copies to sell afterwards - unlike other writers.

So it made sense for me to expand the limited print run for the event, and VLF assured me doing so wouldn't deter a potential publisher because it wouldn't count as self-published. Big publishers normally will not touch self-published novels.

So last week I went onto IngramSpark and ordered a test copy of With Love from the Afterlife. Seeing my first physical copy was exciting but also made me realise I needed to insert a title page, copyright page and Part numbers for the subsequent print run, which will happen this week.

It may be that no one at Cuckfield BookFest wants to buy a copy, and that's fine, although it is a pity I'm having to take on the cost of printing about three dozen copies myself without receiving a penny from Unbound.

But then if you want to make money, being an author is the last occupation you'd choose these days.

It's with a tale of great highs and lows, and a heap of mixed feelings that I will head to the book festival, and I will at last see my debut novel in print.

What anyone will make of it is a mystery to me, because it's almost impossible to see your own work in any detached kind of way. It's almost time for me to become nervous.

Viv Loves Film's authors are listed on its website

Half-born

Publication in itself has been a story full of highs and lows

For authors, sometimes getting your debut novel published is not just exceptionally difficult, it's complicated, too.

My novel is half-born.

And its part-birth has saved me from being dashed on the rocks of despair.

My first novel, which I began when I was eight (so no hyperlink here), made it only to the third chapter, my characters left for ever suspended in crisis mode. But my secret ambition to write a novel and have it published continued to slowly burn, unseen, while I got on with life's usual stuff.

When I finally did finish writing one, I knew little about the art of fiction-writing, and it came out as funny and serious, light and dark, offbeat and unorthodox. Not at all what I'd long imagined my debut novel would be like. It rather took me by surprise.

Knowing agents and publishers were overwhelmed with manuscripts, I was prepared for rejections. But still, when they came, it was of course hurtful. Finally, a small but growing publisher called Neem Tree Press replied saying they loved my draft and wanted to take it on. I was elated. I had waited a lifetime to see a book I'd written in print so this really was a dream come true. And I liked Neem Tree Press. It was an all-women company whose list included work from overseas, as well as novels that did not neatly fit formulas. The founder told me of her ambitions to build a company as large as one of the big five.

But while I awaited my due publication date, without warning came news that Neem Tree was joining forces with a crowdfunding publisher called Unbound. Authors such as me were assured that contracts would be honoured and publication would still go ahead. I wasn't especially happy that my book would appear to the world to be one supported by crowdfunding when it wasn't. But at least the Neem Tree Press name would remain, becoming an imprint of Unbound. It was exciting to see my book on Amazon, marked as due out in January, and on platforms such as Barnes & Noble. Friends started preordering copies on the Unbound website.

However, when my emails to Unbound as well as Neem Tree people started to go unanswered, I suspected all was not well. When even urgent messages were ignored, I realised my hopes were hanging by a thread.

I knew that if the worst happened, I would be devastated. I pictured myself in tears, feeling a failure, curling up into a ball. I couldn't face sending my work out to yet more agents only to receive another round of rejections, adding to the 25-odd I'd already had. Besides, time was marching on, and at the timescales the conventional publishing industry necessarily works to, I would be an old woman before seeing my debut novel in print.

Yet when the confirmation came of the collapse of Neem Tree/Unbound, something else surprised me. I wasn't devastated. I was resigned. The world didn't want to see my life's work and could carry on perfectly well without it. But it was embarrassing that friends and family who had been kind enough to support me by preordering for a copy were now out of pocket, their money swallowed up by the failed Unbound.

A friend who is a successful author of young adult fiction suggested I fund a limited print run strictly for people who had paid upfront but who had lost out. At the same time, another writer friend who is in a self-publishing cooperative kindly invited me to join them. Both friends recommended using IngramSpark, a large reputable self-publisher. It seemed to me that paying for a limited print run was the ethical thing to do.

Neem Tree Press used to work with an entertainment agency, Viv Loves Film (VLF), which specialises in pitching ideas, including novels, to film producers, and, knowing how authors had been left bereft, was keen to take us on as our agent, for which I was grateful. It has given me a further glimmer of hope that With Love from the Afterlife may yet find a home with a publisher.

Before Unbound's collapse, I was signed up to appear at Cuckfield BookFest, on a panel of authors speaking about - aptly enough - the challenges of publishing, a subject that took on more significance after the company's demise. I was likely to be in the unfortunate position of being an author talking about publishing without having any copies to sell afterwards - unlike other writers.

So it made sense for me to expand the limited print run for the event, and VLF assured me doing so wouldn't deter a potential publisher because it wouldn't count as self-published. Big publishers normally will not touch self-published novels.

So last week I went onto IngramSpark and ordered a test copy of With Love from the Afterlife. Seeing my first physical copy was exciting but also made me realise I needed to insert a title page, copyright page and Part numbers for the subsequent print run, which will happen this week.

It may be that no one at Cuckfield BookFest wants to buy a copy, and that's fine, although it is a pity I'm having to take on the cost of printing about three dozen copies myself without receiving a penny from Unbound.

But then if you want to make money, being an author is the last occupation you'd choose these days.

It's with a tale of great highs and lows, and a heap of mixed feelings that I will head to the book festival, and I will at last see my debut novel in print.

What anyone will make of it is a mystery to me, because it's almost impossible to see your own work in any detached kind of way. It's almost time for me to become nervous.

Viv Loves Film's authors are listed on its website